This question is a tricky one to answer and we get it a lot. In the below article, we will do our best to explain. You can always reach out to contact@perch.fit for more info.

Depending on how your clean (or other Olympic movements) “looks” on a given rep, the “pull” portion of the movement may include one or both of the actual pull and catch / stand up portions of the movement.

This has nothing to do with technique, but everything to do with both fatigue and how much weight is on the bar. As you do a set and fatigue, the reps will start to change “shape” in bar path and with mean velocity you may start to get wildly different numbers on the screen for very slightly “different” reps.

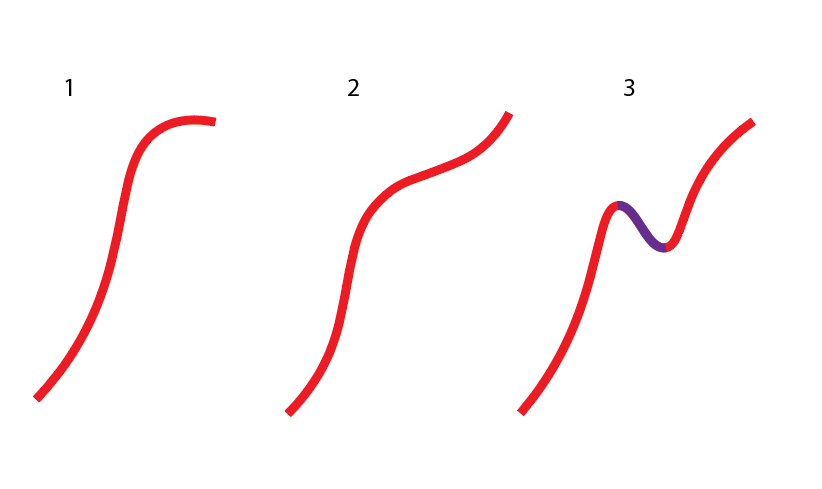

Here are a few examples of how these reps may differ.

Each of the following bar paths represent a hang clean (y-axis is vertical displacement, x-axis represents time). From left to right:

1. This rep has no discernable catch / standup. In this particular case, the movement does not slow down much if at all as the athlete nears the top of their rep which means we only detect a single region of movement, which we consider the pull.

2. This rep has a somewhat detectable catch / stand up, however it is on the wrong side of the thresholds we’ve set and is not getting separated from the pull portion. For this rep, we again identify a single region of movement and deem it the pull.

3. On rep three, there is a very distinct delineation between the pull (first red region) and the catch / stand up (the purple and second red region). As a result, we have detected multiple regions of movement, and separated the catch / standup from the pull. Our metrics would be computed using only the pull portion of the movement since we have been able to easily detect the different portions of the movement.

The problem is best illustrated if you consider each of these three reps as being part of the same set. Since the athlete begins to have a distinct catch after example 2, the catch will stop being included in the calculation of metrics for a given rep. If an athlete was looking at mean velocity for each of these reps on the same set, **their mean velocity would increase significantly between rep 2 and rep 3 despite their fatigue increasing and peak velocity actually going down**.

Now, looking at this particular example you may assert that Perch do a better job tracking.

The reason that is not entirely possible is because there is a smooth continuum of how the bar paths of these reps may appear. The catch could be anything from impossible to discern like the rep number 1 to as obvious as rep 3, but also absolutely everything in between. This gray area is where things break down. Currently, we have not found a way to write the perfect algorithm that will always do exactly the right thing for every single case. In many examples we’ve viewed over the years, there’s not an obvious cutoff point between “there’s no catch” and “there is one”.

Getting the delineation of these portions of the movement correct in the extreme cases is not enough. We can effectively guarantee that athletes using our systems are performing movements that will hover on the boundary between discernible and indiscernible catches, and if you’re looking at mean velocity they will see wildly different numbers.

Peak Velocity

If you look at Peak velocity rather than Mean, none of the aforementioned issues occur. Regardless of what combination of regions are detected during the movement, the Peak velocity always occurs during the pull portion of the lift. As a result, it doesn’t matter what the bar path of a given rep looks like. The Peak velocity will always have occurred during the pull and thus comparing peak velocities across reps will always be valid.

Additionally, by using mean velocity you will be taking into account portions of the movement where the athlete is applying no force to the barbell (e.g. after the second pull and the athlete prepares for the catch).

Finally, peak velocity is a good indicator of explosiveness, the variable we are trying to train with Olympic movements.

Conclusion

Summing up, we have decided that since using mean velocity to measure Olympic movements will yield incomparable results between two very similar reps and research / industry points to peak velocity as great metric for Olympic movements , we won’t let you use mean velocity for Olympic lifts. You just have to use peak velocity.

This conclusion may seem a bit extreme, but we believe it is our responsibility to ensure accurate and reliable data collection. We produce easy to use, accurate, and reliable products with the hopes of powering athletic performance. We cannot do this by presenting bad data. We understand our limitations, and we are owning them to ensure the safety and continued performance improvements of athletes everywhere.

If you have any questions, please contact, contact@perch.fit.